Working-class young people in the north are being failed

Amy Margaret, a young socialist republican activist from West Belfast. A version of this article is also published here.

Over Easter, commemorations were held across the north to mark the sacrifice of men and women throughout history for the cause for Irish freedom. None of these parades or commemorations attracted as much attention as the parade which took place in Derry.

The parade was considered illegal, and so police moved in to the Creggan estate in an armoured Land Rover. A sign was attached to the side threatening that if the parade continued arrests would be made. Young people in the area reacted to these threats by throwing petrol bombs at this heavily armed vehicle.

In the weeks leading up to the parade, police had continuously antagonised the local community, like they do all year round. Naturally, when a hostile police force enters your community and begins making threats, you’re going to react.

However, if you read any of the headlines relating to the event, you would be forgiven for thinking the actions of these young people were in defiance of Biden’s visit or the Good Friday Agreement celebrations. This is not anything new. Any sort of violence or stone thrown in the north tends to be sensationalised. A narrative is created that validates a view on whatever political discourse is prevalent at the time.

The liberal reaction is complete pearl clutching, claiming young people attacking police is a horrific step back to the “dark days”. In recent years, Brexit has been the go-to excuse. Meanwhile, the left, particularly in Britain and the South, frame it as political defiance against an occupying police force and something to be applauded.

Both analyses are frustrating, incorrect, and do a complete disservice to young people in the north.

Deprivation and neglect

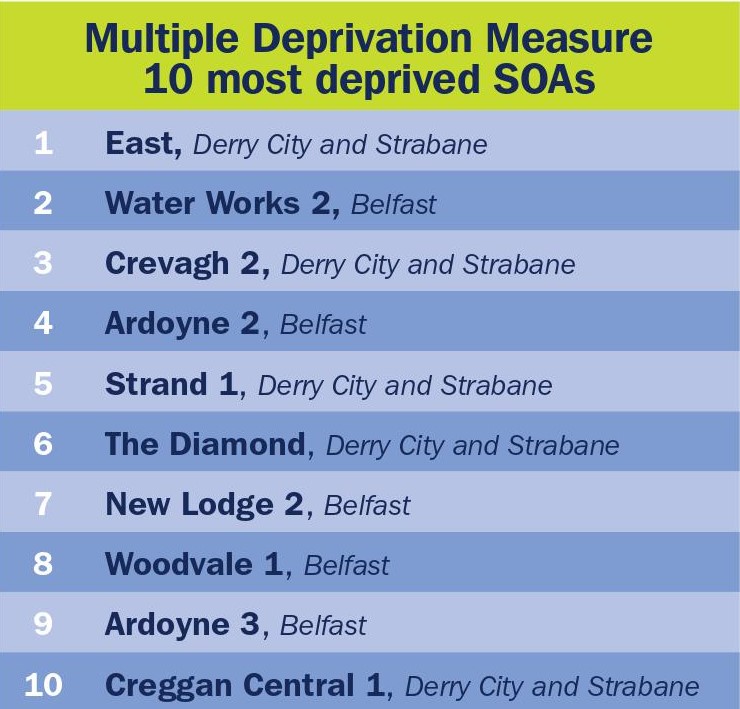

If you were to draw a map of where pockets of violence like Creggan occur, the pins would fall perfectly on the most deprived areas of the north.

According to data collated by NISRA in 2017, New Lodge ranked seventh and Creggan ranked tenth most deprived areas in the north. Young people in these communities grow up with increasing levels of poverty, unemployment, drug problems and suicide. On top of that, there are no social outlets.

The young people in Derry are particularly neglected in this aspect, a perfect example being the Féile. Historically, bonfires were built across the north to mark the beginning of internment in 1971. These bonfires often resulted in antisocial behaviour and placed young people in harm’s way. A dance night was added to the Féile calendar to pull young people away from these bonfires and to a contained relatively safe event.

In Belfast, bonfires on internment night have been eliminated. The Belfast Féile receives a huge amount of funding, attracting thousands of young people every year to dance nights and headliners such as Kneecap. In Derry by contrast, the Féile is underfunded and mostly consists of local acts and family events. While the bonfire issue is complex and not easily resolved, it shows how a lack of investment has exacerbated the problems faced by communities such as those in Derry.

And so, the bonfires continue to attract young people. This isn’t because kids in Derry are more antisocial than those in Belfast. The simple fact is that a bonfire with their mates is obviously a lot more exciting than the alternative.

When a fight is organised on an interface, or a bonfire is built, young people go because it’s exciting, not because of their dissatisfaction with the Brexit protocol or any other political motivations.

This is not an attempt to remove all political agency from these young people. I of course recognise that many will have views on the political situation in the north and young people in the Creggan at Easter were reacting to a hostile police force making threats. I also acknowledge that there are those with influence in the community who are only too willing to use younger people as proxies for their own agendas.

My point is that this is not organised resistance and should not be glorified by those in British left circles who want to LARP, or manipulated by liberals seeking to advance their own self-serving narratives.

Community-led responses, not heavy-handed policing

The reaction of police is almost always heavy handed and exacerbates the situation. At Lanark way in 2021, police moved in to “diffuse” a crowd of teenagers in the nationalist area of West Belfast by firing on them with rubber bullets and water cannons.

In the case of Creggan, the police have a track record of a heavy-handed approach to the community; they know their presence is antagonistic. So, for people who claim they were “just doing their job” on Easter Monday – if their job was to antagonise and exacerbate the situation, they absolutely were.

The people who actually do the job of diffusing and engaging with these young people are youth workers. Youth clubs are the centre of many working-class communities. They’re run by local people and include services such as drug prevention, on the ground response, and simply just a place for young people to socialise.

Despite their importance, in 2022 the Education Authority announced that cuts would be made to youth services in 2023. These cuts have greatly affected youth centres like St Peter’s in West Belfast and St Mary’s Youth Club in Creggan.

Both these youth centres provide on the ground intervention to young people engaging in violent or anti-social behaviour, moving them on before any confrontation with police occurs. However, because of cuts, both centres have had to reduce staff as well as services such as drug prevention and family support. St Mary’s Youth Club faced a 40 percent cut in funding.

This isn’t a situation specific to the north. Young people who grow up in deprived areas the world over resort to anti-social behaviour to entertain themselves and to vent frustrations at the material conditions surrounding them. It just so happens that in the north, we live in a highly politicised and supposedly “post-conflict society”.

So, when young people throw stones at armoured vehicles that only a bomb would penetrate or organise fights on an interface over Snapchat, the solution shouldn’t be to send in a riot squad armed with rubber bullets and water cannons. The people who respond should be youth workers in the local community. With recent cuts they are expected to respond on a voluntary basis, and so police fill a gap.

Working-class young people in the north are being failed. They deserve space to socialise, they deserve to have their voices heard and concerns addressed, rather than being handed over to police.

Comments