Why the EU’s fiscal rules need to be overhauled

“Member States shall regard their economic policies as a matter of common concern and shall coordinate them within the Council.” – Article 103, Maastricht Treaty (1992)

“I know very well that the Stability and Growth Pact is stupid, like all decisions which are rigid.” – Romano Prodi, President of the European Commission (2001)

It is now three-and-a-half years since the EU’s fiscal rules were suspended and state aid rules relaxed in response to the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, which saw governments incur record debts and deficits as a result of increased public spending commitments and collapsing tax revenues.

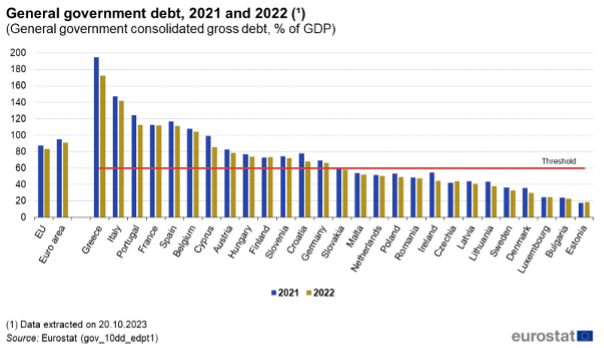

The reimposition of the fiscal rules has been delayed until Spring 2024 due to the impact of the Ukraine war and global inflation shocks, which have worsened the already dire prospects of the eurozone economy. With several member states now carrying debts above 60 percent of GDP and facing higher interest payments, policymakers recognise that debt reduction strategies based on the existing rules (i.e. large scale austerity) would likely trigger a recession across the bloc.

Figure 1. EU government debt-to-GDP ratios (Source: Eurostat)

It is in the context of these post-COVID economic realities that the question of whether, how and in what form the fiscal rules should be reintroduced has become a key battleground in European politics. A new economic governance framework proposed by the European Commission has been on the table since November 2022. However, this has yet to be endorsed by all 27 members of the European Council, with Germany and France still at odds over key aspects of the proposed reforms.

Whereas the former is keen for the EU to retain a strict and uniform approach to deficit and debt reduction, the latter favours more leeway to enable public investment. This debate not only reflects the particular cases of Germany and France, which is coming under pressure to reduce its €3.3 trillion debt. It threatens to deepen existing faultlines between the core and periphery of the EU.

Constitutionalising austerity

Austerity has been a part of the constitutional system in Europe since the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, which laid the foundations for the EU as it exists today.

Maastricht not only redefined the role of the nation-state as member state, making them accountable to one another in key policy areas. It also reflected the ideological consensus of ‘sound money’ advocated by Thatcher’s economists and those of the German Bundesbank.

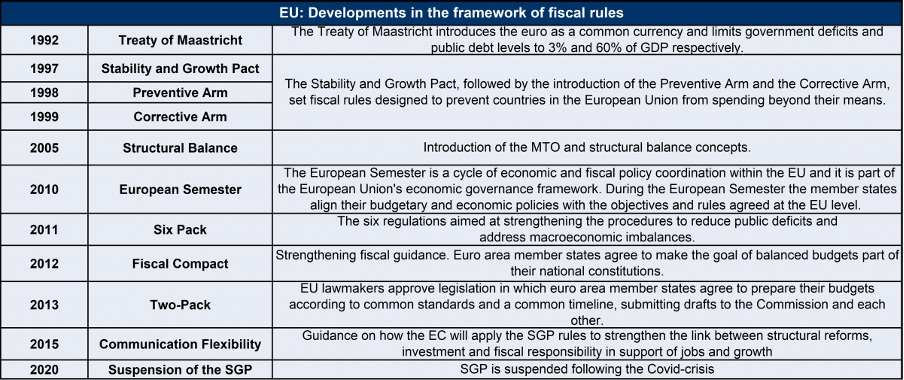

Key to implementing this consensus was the creation of a single currency (the euro) and establishment of the European Central Bank (ECB) to assume control of monetary policy from eurozone members, a three percent budget deficit cap and a public debt target of 60 percent, subsequently enshrined in the 1997 Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) as a binding condition of European Monetary Union (EMU) membership.

The SGP later underwent a series of revisions to ensure stricter adherence to the demands of fiscal conservatism. Notably, the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (Fiscal Compact, 2012) introduced in the wake of the 2011 eurozone debt crisis obliged all member states to enshrine balanced budget requirements in national law, creating a permanent politics of austerity. The Irish ruling class willingly submitted to this agenda, citing reasons of economic necessity and access to future bailout funds.

Layered on top of this Treaty were the “Six Pack” and “Two Pack” reforms, together with the rollout of the European Semester, which empowered the European Commission to scrutinise national budgets, propose changes to economic policy and impose penalties on those with ‘excessive’ debts or deficits.

Figure 2. Evolution of the fiscal rules (Source: ISPI)

With these changes, unelected EU bureaucrats could effectively determine whether a particular government was spending too much on wages, social welfare, pensions or vital public services. They marked the consummation of the neoliberal mode of European integration that had gradually come to dominate since the 1980s.

A lost decade

The eurozone crisis was largely rooted in a structural divide between its constituent economies, with Germany able to run a persistent trade surplus with less industrially advanced southern members on the basis of suppressed wages. The flip side of this was the creation of large trade deficits in the southern periphery that had to be financed by external borrowing from banks in the European core.

Financialisation of the periphery also stimulated increased private borrowing that fuelled property bubbles, most notably in Spain and Ireland. In the Irish case, the large public debt arose from the government’s decision to socialise the losses of commercial property lending by banks, with German, French and British banks heavily exposed.

European leaders reluctantly agreed to bailout packages in order to prevent defaults by the worst affected countries and avert a collapse of the financial system, protecting the economic interests of banks and bondholders in the core. Bailouts in the form of conditional loan packages also allowed Germany to avoid the unthinkable prospect of a fiscal union involving risk-sharing and redistributive economic transfers from the core to periphery.

The EU’s response to the crisis exposed the hollowness of ‘social Europe’. Namely, the imposition of vicious austerity programmes and neoliberal structural reforms had a catastrophic impact on the living standards, development prospects and state capacities of crisis countries, widening existing disparities between the core and periphery. As a case in point, the extent of the suffering inflicted on the Greek people was such that national mortality rates increased by 17.7 percent in the six years after austerity measures were first introduced.

This orthodoxy of austerity was applied to a greater or lesser extent across the continent, underpinned by the interplay between ideology and the drive to shore up capitalist class relations of exploitation through the wholesale transfer of wealth to private capital, both at a national level and within the EU as a whole. It is undeniable that this led to huge increases in economic inequality and social dislocation, helping to fuel the rise of far-right parties and movements.

While benefitting particular blocs of capitalists, austerity was an act of self-immolation that fatally damaged the longer-term prospects for economic growth in Europe. As Yanis Varoufakis explains, austerity not only destroyed consumer demand and with it the conditions for private investment. The area of fiscal expenditure hit hardest was public investment, a key driver of economic activity:

…more than a decade later, the eurozone features lower levels of public investment (as a percentage of aggregate income) than any other advanced economy or economic bloc. And if we exclude Ireland, as we must (given its GDP contains multinationals’ income that the Irish never see), Europe’s economic powerhouse, Germany, comes last within Europe in terms of its rate of overall investment.

The overall impact of this is most starkly illustrated by the fact that the US economy has grown to twice the size of the eurozone’s over the past fifteen years, having been roughly the same size when the crisis hit in 2008. This has left the average EU country poorer than all but two US states and the once mighty European manufacturing sector falling behind its American and Chinese rivals.

The consensus disrupted

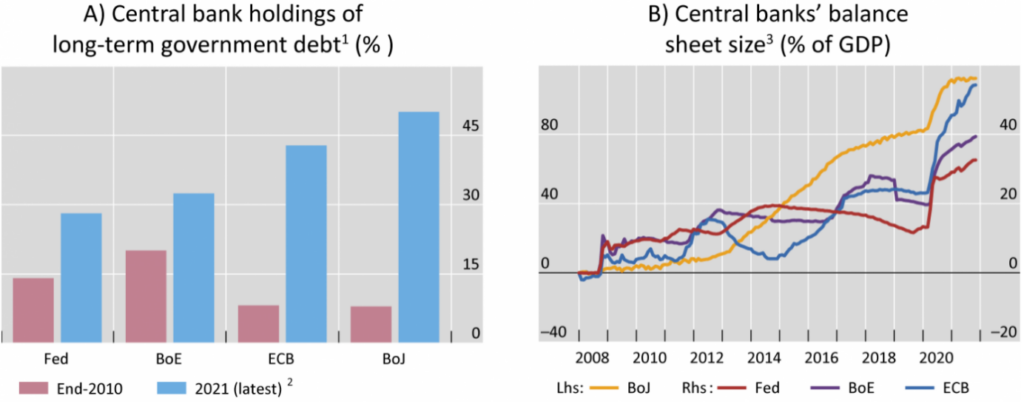

Austerity did not proceed uninterrupted: rather, it was resisted by popular movements and undermined by the contradictory actions of governments and EU institutions during the period. Key in this regard was the famous “whatever it takes” speech by the then ECB President Mario Draghi, which ushered in a massive quantitative easing programme involving the purchase of large quantities of government and corporate debt. This effectively transformed the role of the ECB into a lender of last resort for governments and the financial system: a magic money tree whose job of saving the euro took it outside of its own narrow mandate and the conservative ideology (monetarism) governing the eurozone.

Equally significant was the uneven and inconsistent enforcement of the fiscal rules, which have enjoyed an average compliance rate of just over 50 percent since the SGP entered into force in the 1990s. Successive decisions by the European Commission and European Council over the years appeared to increasingly succumb to political imperatives by granting excessive leniency to the more powerful member states. This reality was spelled out by the European Commission President Jean Claude Juncker in 2016, when he explained in the bluntest of terms that France had been allowed to repeatedly break the rules “because it is France”.

Already on shaky ground, the narrative of austerity as an economic necessity was radically upended by the pandemic. The unprecedented decision to suspend the fiscal rules was matched only by the ECB’s move to buy up a further €1.6 trillion in sovereign debt, taking it firmly into the uncharted territory of financing the deficits of member states.

Figure 3. Central bank bond purchases and holdings of government debt (Source: CEPR)

Together with the creation of an underwhelming Recovery Fund, this intervention by the ECB provided governments varying levels of discretion for increased public spending. Some of this money went to struggling households through pandemic income payments and furlough schemes. Some was used to fund the response of creaking healthcare systems. But largest chunk was provided to businesses in the form of no-strings-attached loans and subsidies. This was on top of the €140bn funnelled directly by the ECB into the corporate sector, inflating asset prices and enriching the extremely wealthy.

The new global economic order

As well as revealing the destructive impact of austerity on public services and welfare states, the pandemic exposed the reliance of capitalist economies on the state. This reliance became even more apparent at the height of the energy crisis, when the further relaxation of state aid rules permitted France and Germany in particular to subsidise energy prices to protect their industries from higher costs.

Europe finds itself in the grip of a perfect storm, at a time of accelerating shifts in global political economy. Public services and infrastructure are crumbling due to years of underinvestment, while the cost-of-living crisis has caused real wages and household living standards to plummet after fifteen years of stagnation. Across the eurozone, key industries are rapidly losing competitiveness thanks to a combination of weak domestic demand, supply-chain shocks, energy costs, de-globalisation and the rise of China, which has been investing in its own technological and productive capacity for decades. Even in the context of a global economic slowdown, the eurozone is facing a particularly bleak prognosis of long-term stagnation.

For their part, the European institutions have responded in a way that has exacerbated conditions of economic and political instability. The EU has hitched its fortunes to the imperial strategy of the declining US empire, committing itself to exponential militarisation and support for endless proxy wars at great financial cost.

However, this geopolitical convergence has not brought about the economic convergence envisaged by European leaders. The switch from cheap Russian gas for expensive American LNG has only benefitted US fossil fuel interests, while the green subsidy package introduced by Biden administration threatens to further erode European industry and drag the EU into a protectionist race it doesn’t want and can’t win.

The ECB meanwhile has responded to a largely profit driven and supply-side induced inflation crisis with interest rate hikes that have massively increased the debt repayments of states, businesses and mortgage holders; and the sell-off of government and corporate bonds, leaving debtors at the mercy of the financial markets.

Resisting austerity 2.0

It is clear that any reimposition of the fiscal rules based on Germany’s hawkish deficit and debt reduction criteria would usher in a new era of austerity that hits the poorest countries and populations hardest, leading to greater economic divergence and political conflict. Moreover, as the New Economics Foundation has shown, even the reforms proposed by the European Commission would deny many countries the necessary flexibility to invest in their citizens and in addressing the climate crisis. The difference between the two positions therefore is the scale of social, economic and ecological damage they would inflict. Needless to say, any third way based on exemptions for defence spending would not represent an advance in any progressive sense.

The stakes today are even higher than in 2008, with depressed economic conditions and accelerating ecological breakdown coinciding with – and helping to fuel – the continued rise of the far right.

Faced with this challenge, and equipped with the lessons of the post-2008 period, the bottom line of the trade union movement and socialist left has to be one of steadfast resistance to austerity – in upcoming elections, on the streets and where the left is in government. This may involve a revival of the short-lived Plan B strategy of strategic disobedience, which aimed for reform of the EU while preparing for a break with it. In this vein, any reform agenda worth its salt must go beyond tweaks to the fiscal rules to incorporate a more fundamental overhaul of the EU’s economic and political governance framework, the role of the ECB and the case for debt cancellation.

Ultimately, the battle ahead will test the dubious proposition that the EU can be reformed into a more progressive (much less socialist) entity, one that delivers a semblance of social, economic and environmental justice for all of its constituent member states. Should it fail this test, increasing unrest and dislocation are likely to follow.

Comments