Follow the profit: How price gouging is still fuelling inflation

Stewart McGill

One of the many profound insights of Marx was that capitalism is driven by the imperative to accumulate more capital. It’s all about the drive for profits: if you want to understand how the capitalist economy works, you need to view it through the prism of that central imperative.

Now this may seem obvious to many of you, but it is less so to those that manage our economy. The Bank of England’s response to an inflation provoked largely by corporate price gouging is to increase interest rates, thereby exerting more pressure on poorer people that have had to go into debt to keep their heads above water and enjoy any quality of life.

Personal debt in Britain rose by one-third in 2022, with over two-thirds of adults (68%) saying that have felt stressed due to the cost-of-living’s impact on their finances this year, and almost half (46%) in debt as a result of the crisis.

In April this year Citizens Advice warned that of a debt time-bomb resulting from the cost-of-living crisis: they were having to help increasing numbers of people with a negative budget i.e. those whose income is not enough to cover essential expenses. According to its latest statistics, 51% of those helped by Citizens Advice are in a negative budget, compared with 36% in 2019. The average debt client now has £0 left over each month, compared with more than £15 in 2019.

“The maths speaks for itself – a household debt crisis is coming and we have a choice about whether to prepare,” says Matthew Upton, the director of policy at Citizens Advice.

Interest rate increases are blunt, misdirected, and more about disciplining labour through fear and impoverishment than fixing inflation.

Food’s robber barons

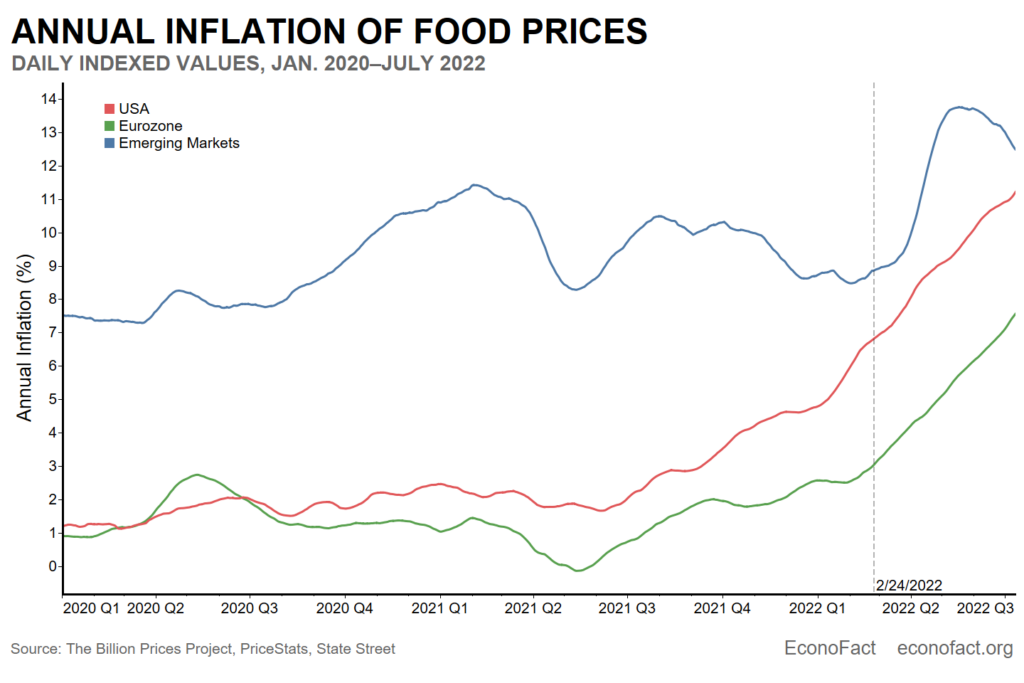

The French government are showing signs of understanding the issue, and even the European Central Bank (ECB) is beginning to realise the true nature of the problem.

French food prices rose 14.1% in the year to May, close to the eurozone average, and have overtaken energy as the region’s biggest driver of inflation. The French Finance Minister announced recently that 75 food producers had pledged to lower prices following weeks of mounting pressure from the government.

The European Central Bank in April, observed that although commodity prices were “falling steeply”, the prices paid by consumers for food “remained very sticky, suggesting that expanding profit margins were preventing inflation from falling.”

The problems in the food industry run deep. We can’t blame it all on the supermarkets ripping people off, though there is still plenty of that.

The big food companies have been cashing in from the cost-of-living crisis that followed COVID, just like the energy companies. The latter tend to be well known: Shell, BP, British Gas and other predators. The names of the businesses pulling the strings of the food industry – Cargill, Louis Dreyfus etc – are less well-known, and much less scrutinised.

“It’s surprising in a way, because I think that they’re doing exactly the same thing as the fossil fuel corporations,” argues Nick Dearden, director of NGO Global Justice Now,

“You’ve got a bunch of corporations that are growing more and more and more powerful all the time, gaining more control over different aspects of the food system and massively profiteering.”

According to a recent report by Oxfam titled Profiting from Pain, food billionaires have seen their collective wealth grow by an estimated 45% over the past two years, with a total of £328 billion added to their profits. In the same period, 62 new billionaires were created as companies inflated their profits by capitalising on the COVID pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis.

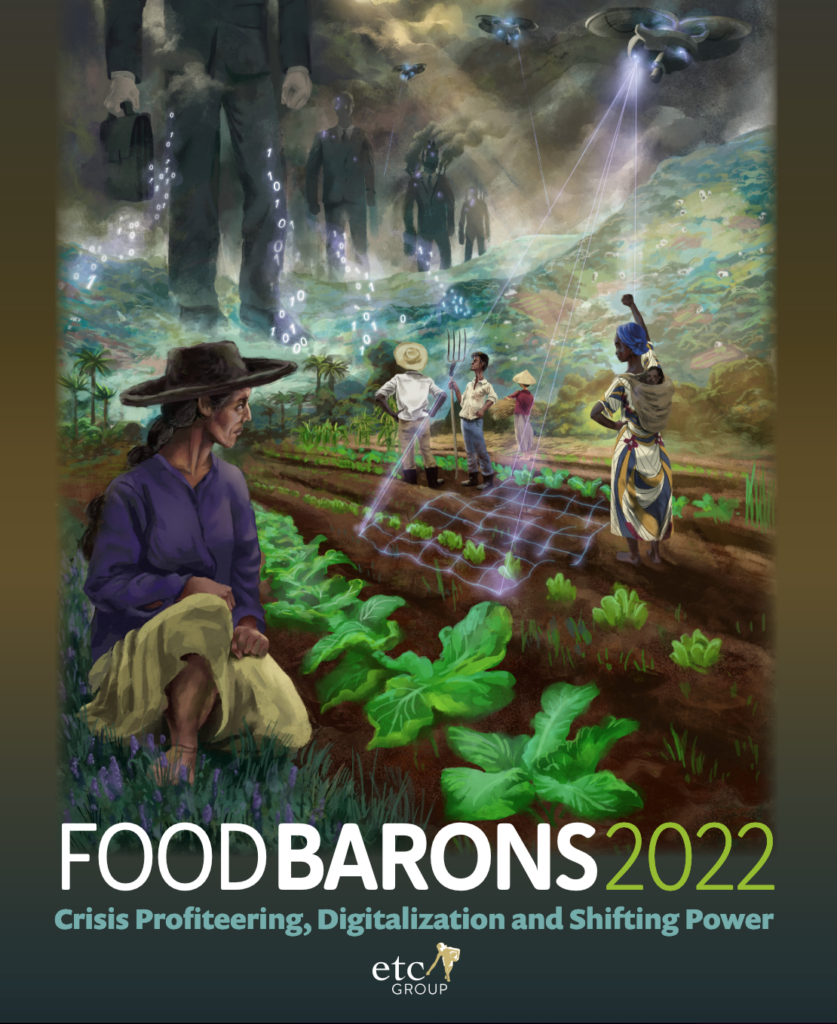

In another recent report on the issue, Mapping Corporate Power in Big Food, the ETC Group identified “just four to six” dominant firms that control every aspect of the food industry, from agriculture machinery to animal pharmaceuticals.

Cargill is owned by the 11th richest family in the world and one of the world’s largest private companies. In 2017, the company was reported among the four oligarchs controlling over 70% of the global market for agricultural commodities. Since 2020, the Cargill family’s collective wealth has grown by 65%, with four members joining the Forbes list of the richest 500 people in the world.

Cargill’s competitor Louis Dreyfus PARIS reported a 44% jump in net profit in 2022.

Nick Dearden sums it up nicely: the food industry is “in a tiny number of hands and effectively controlled on the basis of how much profit those companies can make rather than preventing people from being hungry.”

We need to understand how this market works so we can argue against people that blame inflation on ‘natural causes’ beyond human agency, and the idiots who blame it on workers trying to secure pay increases that prevent them from sinking further into debt-ridden poverty. We also need to understand that, if we want real change and to take control of the commanding heights of the economy, the power of these global giants must be broken and the entirety of the food production and distribution network needs to be transformed. This is also fundamental to saving the environment.

Diesel’s fast and furious profits

No analysis of inflation would be complete without a note on fuel profiteering. RAC analysis has shown that retailers, including supermarkets, have quickened the pace of cutting the price of diesel since the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) expressed concern about weakening competition in the market. In the last two weeks of May, when the CMA issued its road fuel market study update saying average supermarket margins in 2022 had increased compared to 2019, the average price of a litre of diesel at supermarkets fell by 7.44p, from 151.02p to 143.58p. They did this to look better and appear more reasonable in the face of further CMA investigation, and hopefully exposure of their naked profiteering.

The RAC points out that the prices could still fall a lot more, with the average retailer margin on diesel reaching 22p a litre – more than three times the long-term average of 7p.

This hiking up of the price of diesel has a knock-on effect and exacerbates price pressures in the rest of the economy. Combined with the increased price of food provoked by the rapine of monopoly capitalism, this causes wholesale misery.

In the UK alone, more than 30 million people will be unable to afford what the public considers to be a decent standard of living by the time the current parliament ends in 2024, according to a study by the New Economics Foundation. This will be due to rising prices, below-inflation increases in earnings and projected increases in unemployment. Approximately 43% of households will lack the resources to put food on the table, buy new clothes or treat themselves and their families – a 12 percentage point rise compared with 2019.

Conclusion

The idea that companies’ pursuit of profit maximisation will work to the greater benefit of all by means of an invisible hand is one of the stupidest and most dishonest in history. Marx had it right about the way capitalism really works:

“It establishes an accumulation of misery, corresponding with accumulation of capital. Accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time accumulation of misery, agony of toil slavery, ignorance, brutality, mental degradation, at the opposite pole…”

Comments