The rise of the others

Pádraig Ó Meiscill

IN ADVANCE of the new Stormont assembly’s first, and possibly last, sitting on Friday, May 13, a modest head of steam built up behind the idea that the finely-tuned, and completely dysfunctional, sectarian system could be gamed by the Others.

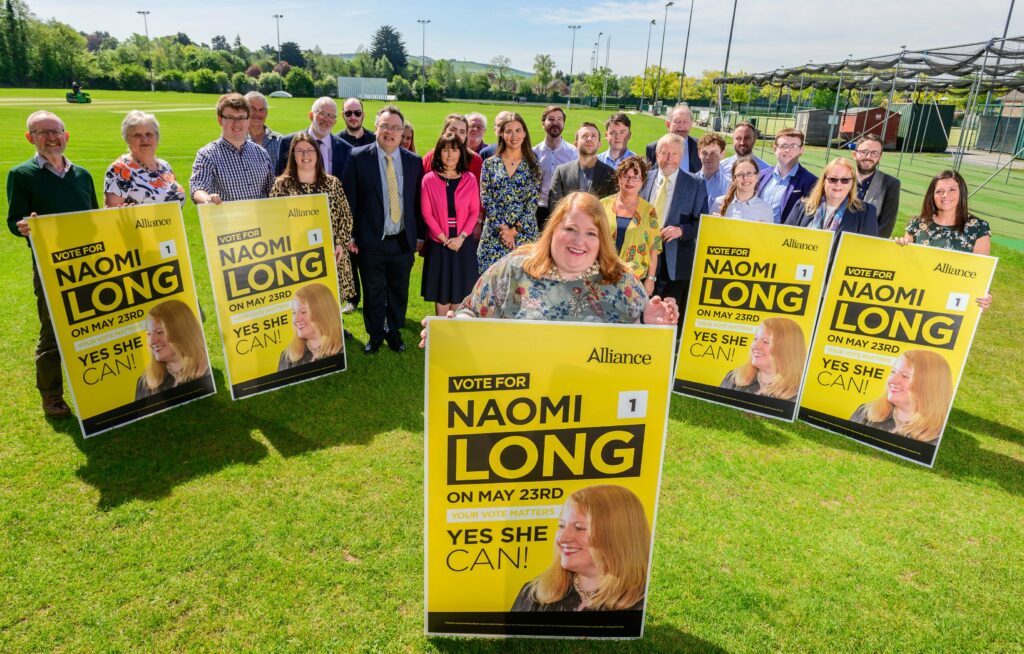

If only the assembly members from the Social Democratic & Labour Party and the Ulster Unionist Party would redesignate as ‘Other’ (as opposed to ‘Nationalist’ or ‘Unionist’), then the Others would have it, went the idea. With the SDLP and UUP now constituting the biggest block at Stormont, in combination with the Alliance Party, they would be entitled to appoint a Deputy First Minister. Naomi Long, the leader of the biggest Other party in Alliance, would rise heroically to the challenge. The obstructionists in the Democratic Unionist Party would be vanquished.

Liberal fantasy

Of course, the idea was but a liberal fantasy. To engage in a charade like that would have put the final nail in the respective oft-varnished coffins of the SDLP and UUP. If voters liked the idea, then why not just opt for Alliance proper next time? If they didn’t like it, then they would defect to the DUP or Sinn Féin. The DUP and their more eccentric mates would have exploded in apoplexy at this latest plot to undermine the Precious Union. In truth, the notion was never taken seriously, the high tide being Long sharing #CoalitionoftheWilling (No, not that one) tweets and laying into the SDLP for refusing to get on board their latest version of the Peace Train. But what the half-hearted attempt did indicate was a desperation among hard-line centrists to get a grip on something they can feel, even at their moment of relative triumph, slipping through their fingers: Northern Ireland PLC, its future destination, its very existence.

Because with enough support behind it, goes the liberal narrative, another Northern Ireland is possible. If enough of us ditch our hang-ups, our bigoted hand-me-downs and the sectarian donkeys we pin our rosettes to, we can walk together into a brighter future of TRIBECA city centres and Tax Free Ports.

The extreme centre

On this reading of things, sectarianism in the northern state exists as a collection of folk myths, bad attitudes and irrational suspicion as opposed to a means of organising power, a system of governance. In this imaginarium, it is the Alliance Party and assorted pals who offer the only way out. In the words of commentator Malachi O’Doherty, the party is “the most credible expression of a non-sectarian middle ground that we have ever had,” which, in a way, is true…. If we interpret this middle ground as the type of extreme centre which has been witnessed elsewhere in the early part of this century.

An attractive option

The Alliance Party performed magnificently in the election of May 5, winning 17 seats and 13.5 per cent of the vote, an increase of 4.5 per cent and nine seats on 2017. The party is clearly an attractive option for many, particularly those from a unionist background weary of the tired reactionary policies and knee-jerk sectarianism of those who presume to own their votes. But, but, but… to state the mathematically obvious, 13.5 per cent of an electorate leaves 86.5 per cent, and that remainder voted almost unanimously for parties which have clearly stated positions on the national question. The other agnostic party of note, the Greens, were wiped out on May 5, losing both seats. Britain’s Irish problem, or Ireland’s British problem, isn’t going away any time soon.

If we are to view election results as barometers of, as opposed to instigators of, change, then those we have from May 5 are obviously useful. The unionist majority – in a state built to foster such a majority for eternity and a day, or at least until The Second Coming – is gone, but what is to replace it is still up for grabs. The North remains deeply polarised between both Nationalist and Unionist camps and the Have-Nots and the Gimme-Some-Mores. The daily reality of working-class people in Belfast and elsewhere remains one of social segregation between nationalist and unionist and economic segregation from the middle class. The economic opportunities which were supposed to flow as part of a peace dividend are nowhere to be seen in neighbourhoods which vote heavily in favour of Sinn Féin and the DUP/TUV. If this might appear a head scratcher, it would make even less sense for the people of Ardoyne or Tigers Bay to vote Alliance, a party with little to no presence in these communities.

Pro-war and anti worker

For many years, the Alliance Party was known disparagingly among nationalists as the political wing of the British government’s Northern Ireland Office. Alliance, compelled by the hari-kari behaviour of mainstream unionism, has undoubtedly moved on from those days of unionist-lite pro-‘security force’ posturing, but it remains a party wedded to a neo-liberal worldview. Witness for example, their voting down of Gerry Carroll’s Trade Union Freedom Bill or their bizarre support for a no-fly zone over Ukraine, which any sane observer accepts would instigate a third world war.

The bigoted hand-me-down

The problem we are faced with is not so much that of how stubbornly voters stick to their ‘tribal’ preferences in this place, but that the prism for resolving our problems is defined so narrowly by the well-to-do. If we are to view the history of the state as a multi-generational struggle for dignity and equality, then Northern Ireland itself is the bigoted hand-me-down, that tired old donkey upon which we are invited to pin our tattered rosettes. And you can hardly blame voters for acting accordingly. And in a society where equilibrium has always meant the exclusion of large numbers of the population, continuing to maintain its precarious balance may not be the best way to proceed, not for those who suffer anyway.

Towards the end of proceedings last Friday, outgoing Speaker Alex Maskey pleaded with assembly members to keep the grandstanding to a minimum. “At least allow the public to get out of their misery,” was Maskey’s polite ask. And if his words, inadvertently, prove to be the last spoken in a sitting Stormont ‘parliament’, they may also be the most prescient.

Outside on the hill, Naomi Long labelled Friday the 13th “a sad day for the people of Northern Ireland,” lamenting on behalf of that imaginary thing which her political trend has tried so hard to bring into being: “the people,” one and indivisible, who will obligingly fit into the liberal construct, shop in a Tribeca city centre, not have the temerity to unionise or strike at short notice, and call themselves ‘Northern Irish’ when asked who and what they are. Unfortunately for Long and the liberals, ‘the people’, the ungrateful bastards, are unlikely to oblige.

Comments