The EU: Proud heir to European colonialism

Stewart McGill

Poland, Hungary and Slovakia announced a unilateral ban on Ukrainian grain imports in the middle of April. At the time of writing, Brussels has just agreed to impose emergency curbs on grain imports from Ukraine to five EU member states. The EU bowed to pressure to reverse its support for Ukraine’s agriculture exports and climbed down from its original position of reminding the east European countries that they had no right to impose such a ban.

The situation was provoked by complaints from local farmers who said they were being undercut by cheap Ukrainian grain flooding their markets. The EU’s restrictions are an attempt to get the affected countries to lift their unilateral bans and avoid confrontation.

Apart from questioning the depth of Poland’s loudly advertised solidarity with Ukraine, this raises many issues about the EU’s agricultural policies that should not be ignored, particularly by those on the left who talk as if the EU is the re-incarnation of the International Working Men’s Association (The First International).

Ukraine’s agriculture and EU integration

On the outbreak of war, much of Ukraine’s grain harvest was redirected into Europe and all tariffs and quotas into the EU were lifted to ensure the grain would not be trapped and go to waste. Unprecedented inflows of Ukrainian wheat, worth €1.17 billion, have crossed into neighbouring EU countries, forcing down local prices, and leaving the produce of many farmers languishing in warehouses. The produce was meant to transit through those countries to international markets. However, much of it has stayed in-country, taking up space in silos and entering the local market.

The surplus has been created by infrastructure bottlenecks – basically lack of cost-effective transport capacity – as well as farmers delaying selling last year’s produce, with local growers holding on to their crop in anticipation of higher prices following the war. A broader global downturn has instead pushed prices down, leaving farmers in Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria facing lower revenue and struggling to empty their stockpiles before the new harvest starts in the summer.

Decreased demand from North African countries, who have had to cut back food imports as their economies weaken in the context of a general downturn and rising interest rates, has also contributed to the crisis.

Some of the most vocal proponents of Ukraine joining the EU are in the eastern parts of the bloc – Poland, for instance. These countries did not think through the implications and the current crisis may have woken them up to reality. What do they expect to happen to the agricultural market when Ukraine is an EU member?

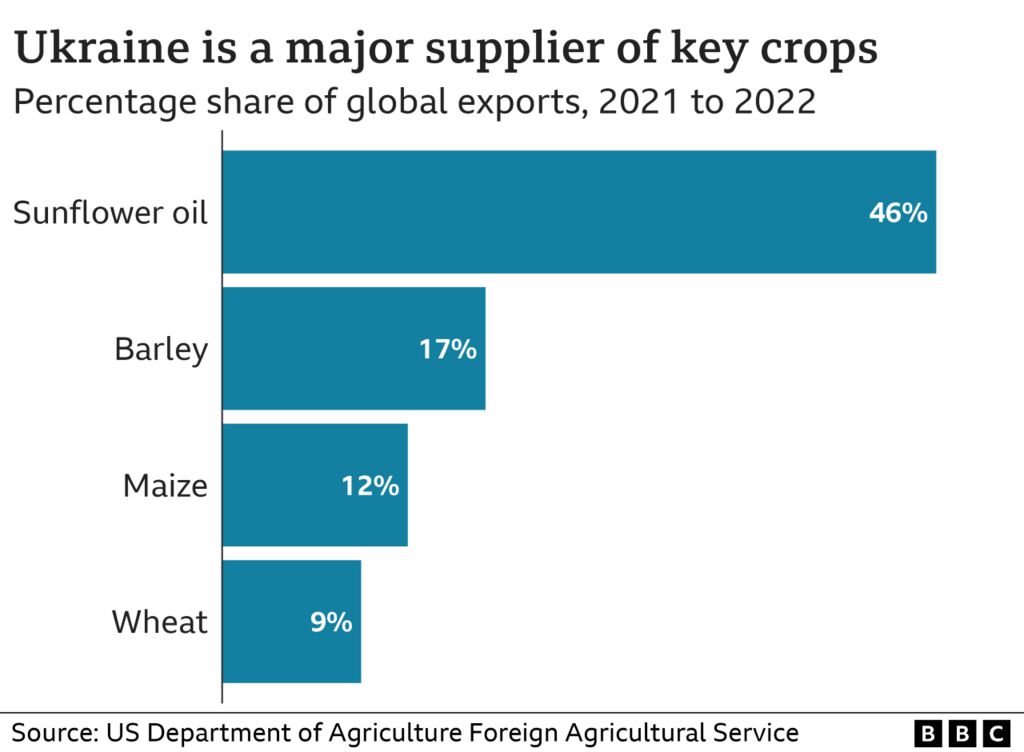

EU states cannot block cheaper products coming from a fellow single market member. Ukraine would become a massive recipient of funding under the Common Agricultural Policy, diverting cash from other ‘deserving farmers’ and probably building an even larger grain mountain. Ukraine is an agricultural giant: before the war, it produced more than a quarter of the world’s sunflower oil, and was in the top ten producers of wheat, corn and barley. In 2022, the Polish minimum wage was €654.8 per month, in Ukraine it was €216.7 per month. You can see why the Polish farmers might be concerned, as should anyone at the lower-end of the wage distribution in Poland.

The concentration of wealth and power in the global North

Just over a year ago we were supposed to be facing a catastrophic global food shortage, politicians and lobbyists were exploiting fears by pressing the EU to relax its proposals to slash pesticide use. Now people are still going hungry but there is a grain glut in Europe, how did we get here?

It’s a long story based around unequal distribution of wealth and dysfunctional markets rigged to benefit the producers in the global North who exercise power and influence over their states and institutions. For decades, farmers in many countries across the global South have been similarly undercut by the dumping of cheap foods onto their markets from rich countries that subsidise food production and export.

Many of those countries have become reliant on food imports, this has left them particularly vulnerable to global market disruptions. These countries are now grappling with rising food import bills and ballooning debt repayments provoking new waves of hunger even as there is a glut of grain in Europe.

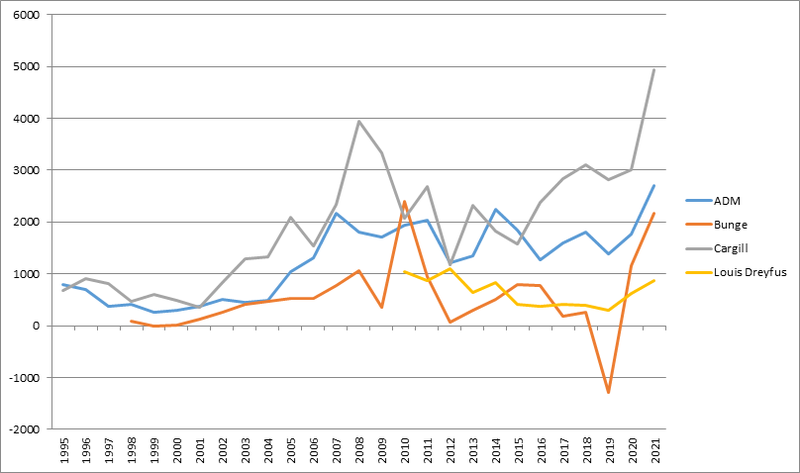

These kinds of outcomes are products of a failing industrial food system that prioritises the over-production of few staple food commodities for globalised just-in-time supply chains; and that encourages monopolisation by just a handful of agribusinesses – like the grain giants who saw record profits this past year.

Only four corporations—ADM, Bunge, Cargill and Dreyfus—control more than 75 percent of the global grain trade, this is a dangerous global oligopoly that will need to be destroyed, not ‘reformed’, if real change is to be achieved.

World agriculture that is run in the interests of those agribusinesses and the global North in general systematically fails to get food where it is needed, prevent rising hunger, or deliver stable livelihoods for farmers.

EU policies hurting the global South

The EU’s agricultural policies are a major part of the problem and expose the fundamental nature of a bloc dedicated to facilitating exploitation by the rich. Those who come out with the ‘reform from within’ fantasies fail to understand that this is the raison d’etre of the EU.

Africa has large amounts of fertile land, but it struggles to make its agricultural sector profitable, leaving most African nations net importers of food. The continent imports roughly 80% of its food, spending more than $70 billion each year on staples, including maize, wheat, rice, soya and milk, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

The European Union (EU) is the biggest exporter of food to Africa, selling food products valuing nearly $20 billion to the continent each year according to European Commission statistics. Subsidies enable farmers in the political bloc to sell agricultural products at prices that don’t cover production costs. Most of these foods – wheat, milk powders, cereals, vegetable oils, poultry and vegetables – could be easily grown on African soil but unfair trade agreements give EU farmers an enormous advantage over their African colleagues, according to the FAO.

Free trade deals between the EU and some African, Caribbean and Pacific states known as the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) gives the EU cheap access to up to 83 percent of African markets. In exchange, the EU offers to eliminate certain tariffs and duties. Industry experts have repeatedly criticised the deals, saying they primarily benefit the EU because African companies are too weak to compete with European firms in a free trade environment. When Kenya, for example, refused to sign a deal in 2014 out of fear that subsidised agricultural products from the EU would ruin its food sector, the EU threatened to impose import tariffs on one of the country’s biggest foreign exchange earners, the cut flower sector. Kenya gave in and signed the agreement.

“African countries cannot compete,” according to the UN economic analyst for East Africa, Andrew Mold. “As a result, free trade and EU imports endanger existing industries, and future industries do not even materialise because they are exposed to competition from the EU,” which affords little incentive to enter the market.

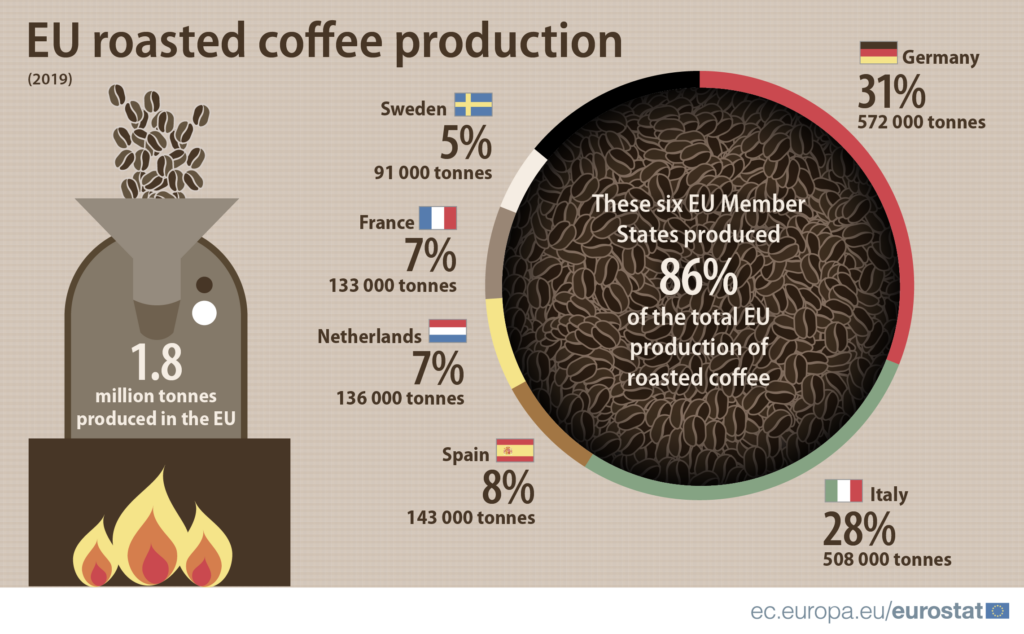

High EU import tariffs on processed foods force African farmers to export agricultural products raw, instead of adding value to them to increase profits. Raw foods that cannot be grown in Europe, such as coffee, are exempt from tariffs, while roasted beans have a 7.5 percent surcharge.

As a result, Africa, a key coffee grower, earned $2.4 billion from the sale of green coffee beans in 2014, while Germany earned $3.8 billion from coffee re-exports after roasting the beans according to Calestous Juma, Professor of International Development at Harvard University: “The concern is not that Germany benefits from processing coffee. It is that Africa is punished by EU tariff barriers for doing so.”

If Ukraine were to join the EU, it wouldn’t just damage farmers their east European neighbours. An agricultural superpower armed with EU subsidies would inflict even more neo-colonial damage on Africa. This is more akin to the quasi-imperialism of the Second International than Marx’s original First International that some on the left mistake as the EU’s inspirational ancestor.

Comments