The nostalgia of Derry Girls and the politics of hope

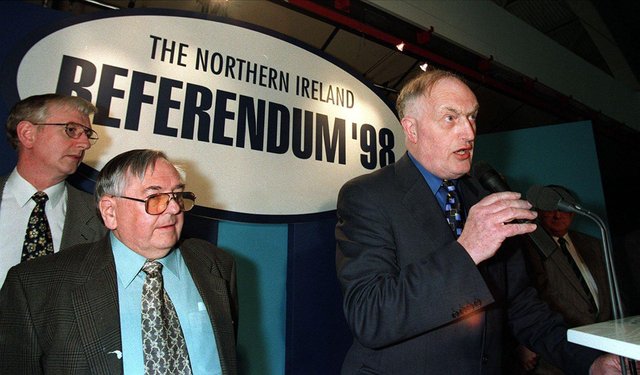

Brian Christopher and Maev McDaid

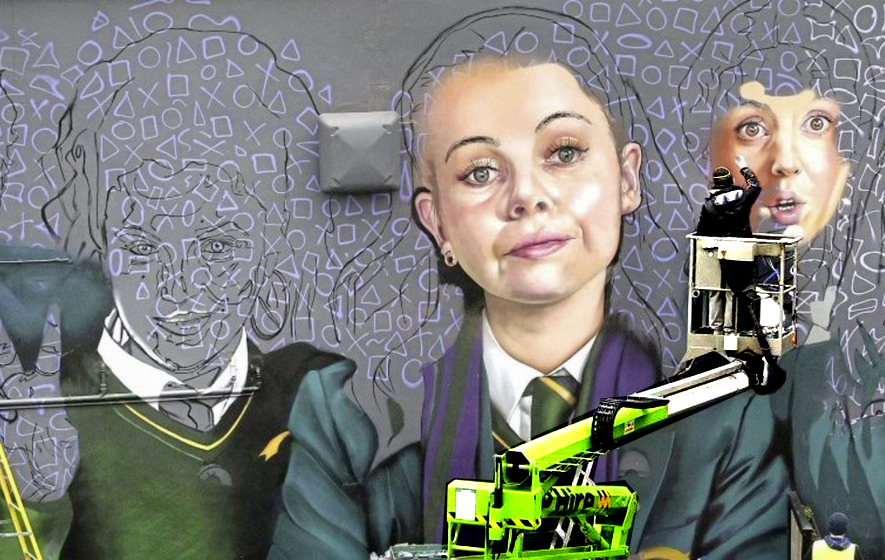

LIKE everyone else we eagerly anticipated the Derry Girls finale last night of what has been a thoroughly enjoyable three-season coming-of-age story, set against the backdrop of the conflict. We were children of this era, being 11 and 14 when the Good Friday Agreement was ratified in 1998. Part of the nostalgic charm of Derry Girls is that, while we were very aware of growing up in extraordinary circumstances, in a city of huge importance, like its characters, we were also just young people wanting to enjoy life. However, something that was particularly interesting about last night’s episode was the focus on the hope of the Good Friday Agreement. This gave us pause for thought – is this something people can still be hopeful about?

Cynicism and Crisis

The Agreement passed with over 71% of the vote and thus represented a hugely historic occasion of which we have no reason to downplay despite our criticisms of it. However, it was only supposed to be a temporary agreement and 24 years on, hope has been replaced by cynicism as Stormont enters yet another crisis. How can something that purported to offer and promise so much fall so flat? The GFA remains the blueprint for (mis)rule in the North of Ireland. We argue that it has not delivered on the promise of an equal and just society for all its citizens. And yet to criticise the Good Friday Agreement and its present day failures evokes all manner of backlash and horror.

Sub-contracted decision-making

Until recently, anyone who suggested that the Good Friday Agreement wasn’t scripture, could be called dissident or accused of wanting a return to old rivalries. While problems within Stormont, and the frequent collapses of Government are part of the daily conversation, few seem prepared to go so far as to locate those issues in the nature of the Agreement itself such as that old rivalries are enshrined in the very essence of the Government. An executive formed of three or four parties has never managed to agree a programme for government and pressing through legislation requires majorities in both ‘nationalist’ and ‘unionist’ designations and is subject to the veto of a ‘petition of concern’. Those who call for ‘making power sharing work’ neglect this reality and so are bound to face its brick walls sooner or later. While the GFA was seen as the way of empowering Irish people through devolution, it seems the outcome was to sub-contract just enough decision-making power to make self rule seem possible. This is a myth is shattered if we look at the case of abortion.

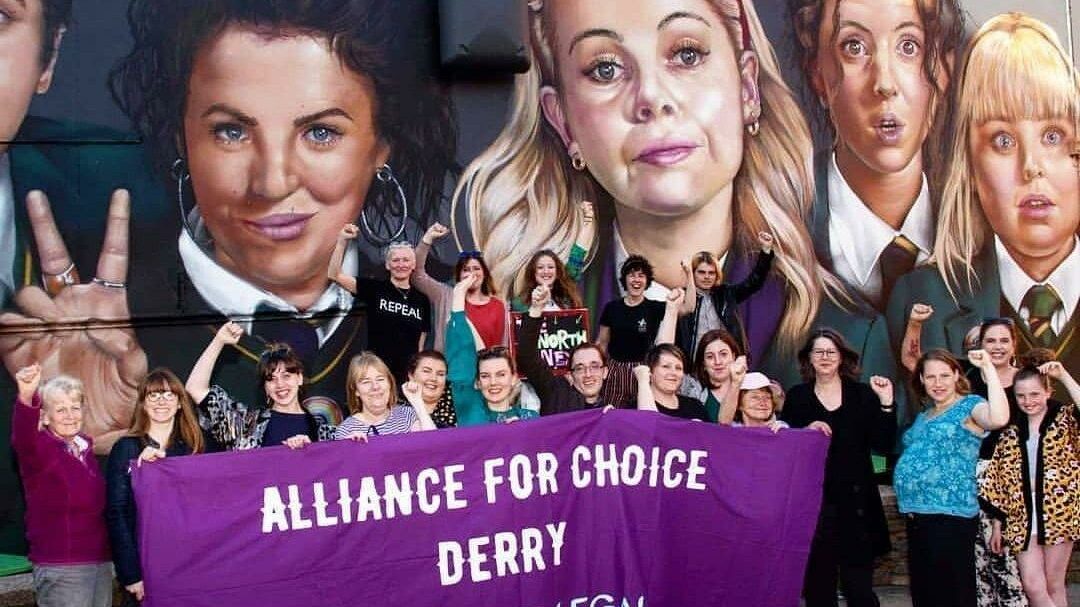

Change and hope has always come from the street

If any of the Derry Girls had fallen pregnant in the 1990s – and many did – they would have had to take the boat or plane to England – or continue with an unwanted pregnancy. This is still the case in the present day for despite abortion being decriminalised, there is still no access. However, we must ask – where did the decriminalisation come from? In 2018 Westminster voted to decriminalise abortion in the North of Ireland. We obviously welcomed the opportunity that the law would change, albeit, through more power to civil servants.

The failure of Stormont

However, it should come as no surprise to anyone who is aware of the complexities of Ireland that dictating solutions from Westminster – whether it be our erstwhile borders, our recognised languages or the health of our bodies – falls foul of the most basic democratic standards. And the vote happened in Westminster because of the total failure of Stormont to represent the people of the region. So when the Good Friday Agreement fails to deliver a democratic and representative body what choice do people in the North have? We need something else to be hopeful for. For those who think voting every couple of years (and the North has had more elections than any other country in Europe in the last 20 years) is the most important or only way to affect change they’re obviously mistaken. Change and hope has always come from the streets and never has this been more represented by the abortion campaign across Ireland.

A dangerous relationship

We are concerned about a dangerous relationship where a precedent has been where London is expected to solve our problems because the GFA doesn’t deliver. Westminster acted because of the strength of the people power movement on the ground that has been relentlessly demanding better rights. It should have meant that people in the North who need *and* want abortions can have them and that has still not happened. Despite the obvious, difficult, constitutional crisis that is ongoing in this ‘United Kingdom’, particularly for those of us in the North with no representation, peoplepower is breaking through and forcing decision makers to act and we still see no results – our hope should not be in Stormont nor Westminster.

We remain deeply concerned that anyone can in the long term see our reproductive freedom, and indeed any of our civil rights, as something to be gifted to us through a vote in Westminster as the solution to the democratic deficit. Any event where Westminster legislates for us takes place in a specific context that has been brought about by Britain’s imperial relationship with Ireland. Westminster has created the crisis in North and us *having* to demand Westminster for our civil rights exposes the contradictions, where they have denied them thus far.

A back door to direct rule?

Way before Brexit, our society was crumbling under sectarian polarisation and austerity. We aren’t changing our society waiting for it, we are changing our society by organising in the streets – strikes, direct action, popular mobilisation – it’s just really ironic that under the circumstances the change will be enforced by the very institution that has holds a colonial power over us.. The same people power must be used to ensure that this does not become a back door to direct rule, because while Westminster might legislate the right thing today, next week it could be implementing further austerity or passing through a harder border.

Complex identities

One of the best things about Derry Girls is its ability to show complex identities, from ‘the wee English fella’ at a girl’s convent school to Mary the housewife who secures a place at university. We have always been more than just Catholics and Protestants. But the real dividing line in our society is between those who have power and wealth and those who struggle against it. Now, long after 1998, it is our time to question – what power has the GFA agreement delivered and the conclusion is that we must demand better.

Brian Christopher and Maev McDaid are Derry natives, Derry Girls fans and live in England.

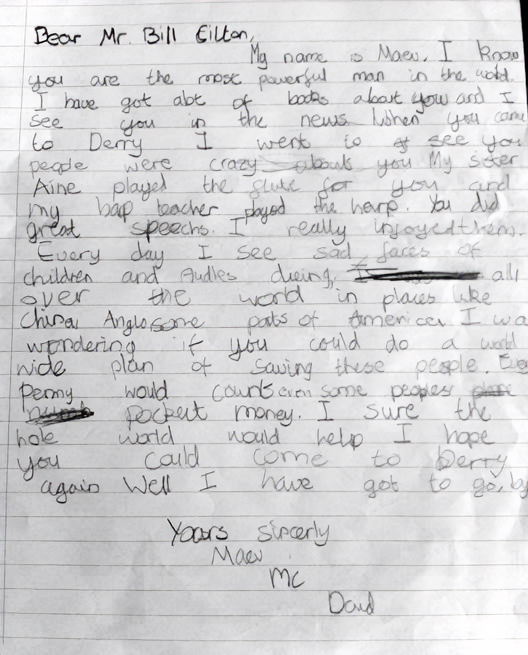

This is a letter Maev wrote to Bill Clinton when she was 9 and a time Clinton fever was rife throughout Derry. While Maev has grown up some politicians have not. The politics of hope from a young Derry girl shattered through experiencing the reality of lack of rights under the GFA.

Comments