Why are we being told there is less inequality?

“Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!”

So said the Wizard of Oz in the iconic movie of the same name. He was trying to convince Dorothy and her friends that he was an all-powerful wizard, until her pet dog, Toto, pulled back the curtain exposing the wizard as just a “humbug” lever puller attempting to preserve the status quo and maintain his unearned position of privilege.

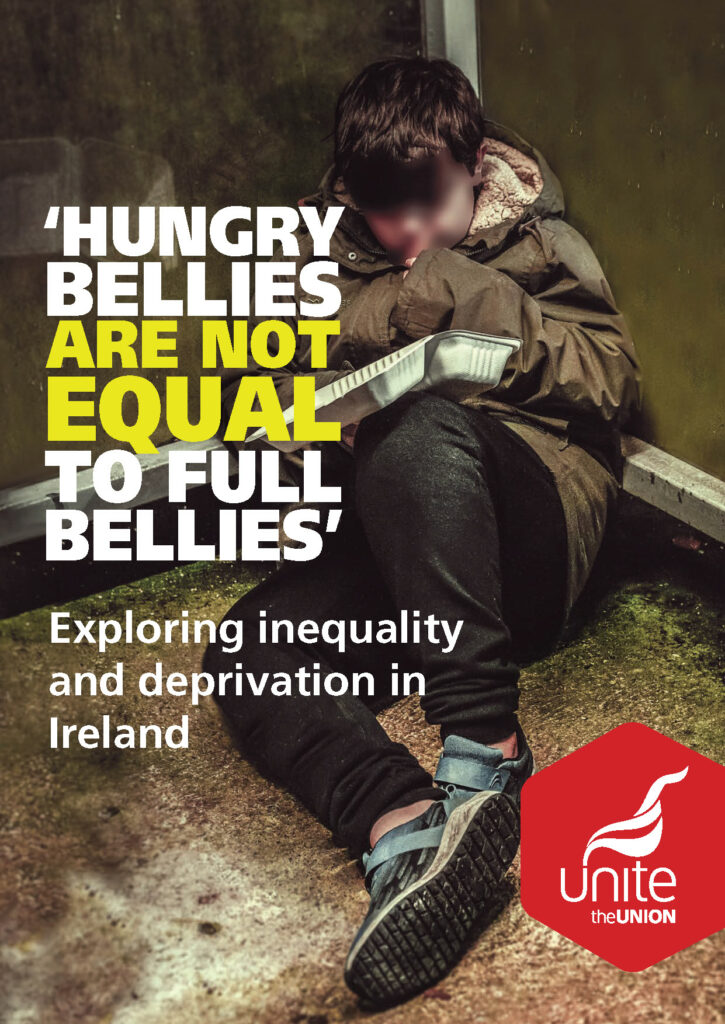

Unite’s document last year, Hungry Bellies are not Equal to Full Bellies, is Toto in our scenario.

This report strips back a curtain of lies and inaccuracies, exposing the truths about inequality and how economic power maintains itself in Ireland. Before we get into the detail of the document itself, here is an example of the cultural context which makes this piece of work an important counterpoint to prevailing narratives.

On 19th November 2020, economist Seamus Coffey, of University College Cork, published an article on RTE’s Brainstorm website headlined “Why has income inequality fallen in Ireland?”

Firstly, it might interest you to know that it’s not necessarily true.

Despite this, it led to Irish Times political editor Pat Leahy writing an opinion piece on 5th December entitled: “Ireland is becoming more unequal? Wrong.”

Ideology at work

This opinion piece, in turn, entered the realm of decision makers, through Fine Gael Senator Jerry Buttimer putting on the record that inequality was falling.

“I remind the House of Mr. Seamus Coffey, the eminent University College Cork academic who has written on the issue of income and inequality. The reality is that income growth and inequality is falling in our country at this time and as Mr. Pat Leahy wrote recently in The Irish Times, people are getting richer and we are becoming more equal.

“If, however, one was to listen to the chorus and crescendo of naysayers, one would think we were living in a Trumpian world where government did nothing and our people were getting poorer.”

Thus, a narrative in line with preserving the present order is maintained. This is ideology at work.

Understanding this process is important. Inequality, particularly to those experiencing the harsh end of it, is important. A report from the Institute for Public Health just over 10 years ago showed that in Ireland we have over 5,400 preventable deaths every year from economic inequality. That’s more lives lost in one year than were lost during the 30 years of the Troubles. So to play around with inequality data and present it as something it is not is a political deflection which, due to its impact on policy makers, potentially costs lives.

If the agenda suits…

The Unite report, drafted by Dr Conor McCabe, dives into the inequality data in detail. It explains using a comprehensive evidence base how Seamus Coffey and Pat Leahy both use limited data to present an argument that suits their own agenda. For example, income inequality is often, erroneously, used as a representation of inequality itself. But income inequality isn’t economic inequality. It’s one aspect of inequality. Conveniently it ignores wealth; public services; tax; capacities; family composition; and costs of goods and services.

Think about it like this: a worker in Ireland might have the same net pay as a worker in Denmark, but the worker in Denmark spends €50 a month on childcare due to public subvention and the worker in Ireland spends 20 times that at €1,000 a month. Who is better off?

Incomplete Data

Moreover, when income inequality is used as a metric of assessment alone, this is using incomplete data which focuses on the Gini coefficient. In Ireland’s case, as the report points out, it “is not based on information on the 1.7 million households in the state but on a small sample of them – 4,183 to be exact (around 0.2 per cent of the total).”

The CSO asked 9,000 households to participate in the survey with only 40% agreeing. Evidence shows that high income households are the most likely not to participate, so you’d think everyone should be made aware of that serious flaw.

That’s not factoring in that 50% of those who answered the survey were proxies, that is, ‘another resident of the household due to unavailability of the person in question’. Nor is it factoring in that there are two methods of calculating income inequality, one (Gini coefficient with all its flaws) showing it falling and the other (tax returns of top 1% based on over two million tax units) showing it increasing.

The fact that Coffey and Leahy argue that inequality is declining in Ireland while wages are increasing will jar with many of our readers who know instinctively, and from lived experience, that this is not true. You start to question, “am I the anomaly?” when you hear that everyone is doing so well. The truth is, again, as pointed out in the report, deprivation is on the increase in Ireland.

People experiencing enforced deprivation is up

Let’s quote directly from the Unite report: “On September 2nd, 2020 the CSO published a report which found that the enforced deprivation rate in Ireland had increased in 2019 to 17.8%. Enforced deprivation is defined as not being able to afford two or more deprivation indicators such as keeping the home adequately warm or buying presents for family/friends at least once a year, said Eva O’Regan, Statistician with the CSO. ‘The percentage of people considered to be experiencing enforced deprivation in 2019,’ she added, was ‘up from 15.1% in 2018’.”

The same CSO report found that 34.4% of those in rented accommodation were in deprivation, up from 27.4% in 2018. Women were more likely to experience it, while over one in five children were living in deprivation.

It also found that the proportion of the population experiencing three or more types of deprivation items increased from 9.9% in 2018 to 12% in 2019.

The Unite report goes into detail in relation to why Irish data is skewed significantly when you only factor in “income” as your inequality qualifier. Whereas other countries in the EU invest heavily in a public housing and public healthcare system, Ireland’s social welfare system, for ideological reasons, is a largely monetary one, i.e. they give you money and tell you to source your own accommodation and healthcare from the private market.

A holistic perspective

If we want an accurate understanding of inequality, we need a holistic perspective.

As Dr McCabe said: “Put bluntly – whatever your wages, if you have no money left after rent/mortgage, food, bills, taxation, healthcare, transport and supporting your family then you are poor.”

The importance of the Unite report cannot be understated. Everyone should read it. And we should all feel empowered to challenge the authority of public figures, or political experts who tell us what life is like in Ireland when the lived experience of workers is completely different.

It is important that we challenge received wisdom by thinking through the relations of how things are. The simple way to think of this question is to ask ‘Do they have skin in the game?’ To not do so would be to allow the Wizard of Oz to maintain his privilege at our expense.

Senator Buttimer said in his statement to the Seanad floor: “Can we ever get a bit of honesty from the political commentariat in our country and from some – who are not in this Chamber now – on the extreme left who have no idea what they are taking about?”

Indeed.

Comments