Why Ireland needs a Living Wage and Universal Services

By Ciarán Nugent

Inflation has workers poorer. It might take years to recoup the losses.

There have been three statistical releases related to the Irish labour market and Irish living standards in the past number of weeks; one on employment, another on earnings (both with data up to September) and another on material deprivation covering the first six months of 2022.

We’ve seen employment growth come to a halt in the third quarter this year, though the estimate was still up by 80,000 over a year, most of which was full-time work. This is impressive growth relative to any time over the last three decades.

Strong growth in high-end sectors like IT and Professional, Scientific and Technical activities last year (both are about 5% down on their peaks in the final quarter of last year) was followed in more recent quarters by strong growth in Retail, Construction, Administrative and support services and Hospitality.

We’ve record numbers in employment as well as a record share of working age adults in employment. Almost two-thirds of the 200,000 or so new jobs since 2020 have gone to workers over 40 and growth was particularly strong for women resulting in the highest female employment rate in Irish history (though the rate for men has yet to recover to levels in 2007).

Although unemployment for younger workers dropped in 2021 to the lowest ever rate, it’s back up again to around what it was in early 2019. This rate had also not recovered from the financial crisis post 2008. The last time before that youth unemployment was so high was in March 1998.

Plenty of room for wage increases

The new wage data shows that average wages grew this year by over 3% but have not nearly kept up with 8.7% inflation. Only IT, which accounts for 7 or 8% of employment saw average wages grow ahead of inflation (by about 2%). That’s one sector out of 14.

Average wages for Irish workers fell by almost 6% this year both on an hourly and weekly basis.

This has affected public sector workers more with real hourly wages in public Education down over 7% in the year and 3.7% lower than the same period in 2019. Public sector Health workers are also down over 7% this year and 1.7% on 2019 in real terms, the Gardaí by 8.1% and 3.1% relative to 2019. The average Civil Servant is down 9.4% in real terms per hour this year.

Real wages are also down in low wage sectors; 4.4% in Hospitality and almost 7% in Retail.

There is little evidence to suggest that a wage inflation spiral is a potential issue at present. There is plenty of room for wage increases, particularly in the bottom half of wage earners.

Over three years, due to inflation real average weekly wages in Ireland are up just 1.6% and if these trends continue, will be lower by the end of the year than they were pre-pandemic. This is already the case for the new minimum wage coming in in 2023; €11.30 (to be brought in in January) is worth less in real terms than €10.10 was in January 2020. The drivers of the current inflation show no sign of abating and there’s no reason to believe they won’t continue well into 2023 and probably beyond.

The economy isn’t “overheating”

Although we hear a lot about overheating (this was even highlighted as a concern by many economists in public commentary in 2018/2019) there is little evidence in the most recent data to support this either. Overheating is kind of code for “we’re worried that the bargaining power of labour is getting too strong and wages will grow too strongly”. When there are less jobseekers than jobs, employers have to compete for talent by increasing wages. When it’s the opposite, more unemployed are fighting over scarce jobs and employers have more power over dictating wages.

With employment numbers and employment rates dropping off slightly in the last round of data, it seems even less of an issue now. One measure of importance is the job vacancy rate (the share of vacant jobs in a given week per thousand). Ireland consistently has a rate at about half the EU average and this didn’t change at any time over the pandemic. The latest data show 1.6 jobs vacant per thousand. It’s 3 on average in the EU. It’s 5 in the Netherlands. At least by this measure we still have a relatively sluggish labour market in European terms.

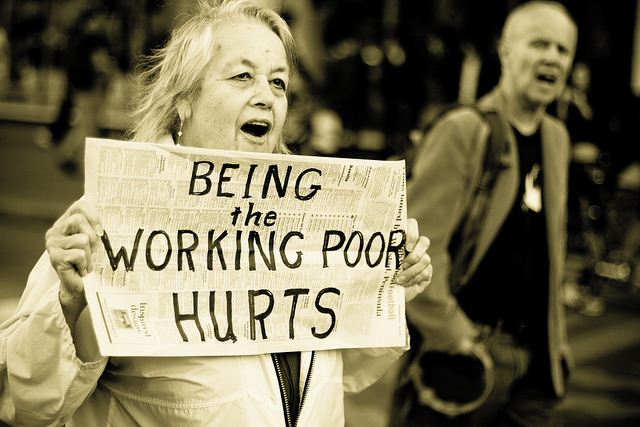

Material deprivation is rocketing

The third survey with results published in recent weeks is from the Survey on Income and Living Conditions with a special module on enforced deprivation. Surveyors from the Central Statistics Office ask thousands of households if they can afford what are considered 11 basic necessities (a second pair of shoes, a winter coat, a night out, a week holiday). A household is considered to be in deprivation if they can’t afford two or more on the list.

This estimate of Irish citizens struggling with the basics increased by over 150,000 to 860,000 in 2022 or 17.2% of the population (more than 1 in 6). This included an increase of over 100,000 additional workers to 288,000 an increase of 60% in this predicament. That’s 1 in 12 workers to 1 in 8 in the space of a year despite almost record employment growth. 1 in 8 Irish people are in ‘extreme material deprivation’ and can’t afford 3 or more of the 11 items on the list.

This particular indicator does not capture all material deprivation however. It does not include 62% of 18-34 year olds living with their parents and deprived of independent living (though there is likely some overlap). The share of 25-34 year olds (mostly highly educated) living at home doubled between 2012 and 2021 (to more than 4 in 10) in Ireland. The EU average didn’t change. This is the highest share since we started counting in 2003. Over 6 in 10 of this group work full-time and the share of working young people living at home has been trending upwards for several years. Only 1% of Irish adults under 30 live independently, the second lowest share the OECD.

Of course, we saw similar trends in the years before the pandemic and almost identical jump in deprivation numbers in 2019 with excessive housing costs driving these trends. In 2022, over 1 in 3 renters couldn’t afford the basics and 1 in 5 had gone without heat at some stage this year, the latter up by 50% on 2021. The share of workers receiving housing assistance payments is now over half of recipients. The government recently announced an increase to minimum eligibility for social housing applications to €40,000 for a single adult. Median earnings in 2020 were €32,708. 62% of Irish workers would be eligible for social housing if they were single!

We have the 2nd highest wage inequality in the EU, one of the highest shares of low wage workers in the EU and we’re an outlier in market income inequality at the household level.

There is a clear mismatch between wage growth and increasing living costs. Renting a new place is up 14% this year. Falling living standards should be tackled both by increasing wages to a Living Wage in the short term and tackling living costs in the short, medium and long term; build social housing, tackle vacancy, tackle short-term lets, retrofit the built environment, roll out renewables (to get away from fossil fuels generally), make childcare public, expand public transport and make it free at the point of use.

Comments